Indigenous Cartography and

Cartography of the Indigenous

Cartography of the Indigenous

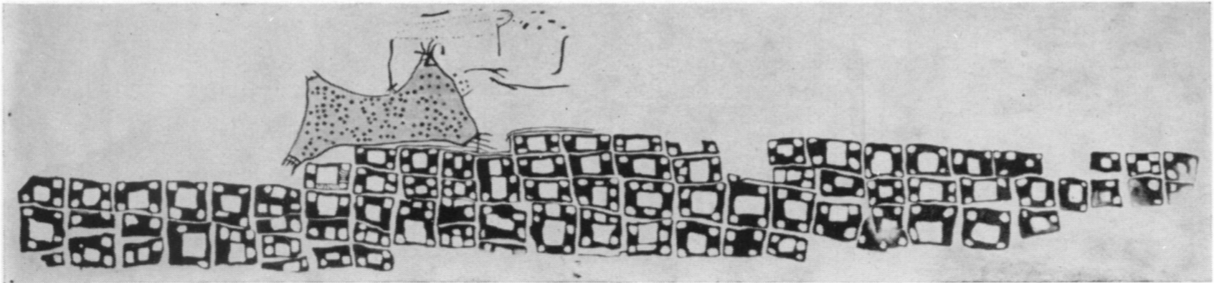

Peter Skipper (1988?). "Water Holes at Jila Japingka and Pajpara with Parallel San Hills" in "Dreaming in Acrylic: Western Desert Art", Anderson, C. and Dussart, F. in Dreamings: the Art of Aboriginal Australia, Peter Sutton (ed). USA, the Asia Society Galleries and George Braziller Inc. fig 141a.

"Maps are graphic representations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world."

Harley, J.B. and Woodward, D. (1987). "Preface" in The History of Cartography - Volume One: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean, Woodward and Harley (eds). Chicago, University of Chicago Press. P. xvi. https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/index.html.

What is a Map?

- Maps tell stories ...

... the story is about place and space - Maps are representations of reality

Location and attributes: spatial relationships

- Maps are performances

... and they have purpose - Maps are abstractions

symbolization and generalization

The 6200 BC “map” of Çatalhöyük in Turkey

Is this a Map?

National Geographic made the map of the US based on translations of place names from their origins in Native American languages.

Lewis, G. Malcolm. (1998). "Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans" in Harley, J.B. & Woodward, D. (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

"kinds" of maps ...

-

Rose-Redwood

- ancestral

- anti-colonial

- de-colonial

-

Luchessi following Fredlund

- biographical

- ceremonial

- message

- trade route

Rose-Redwood, Reuben, Barnd, Natchee Blu, Lucchesi, Annita Hetoevėhotohke’e, Dias, Sharon, & Patrick, Wil. (2020). Decolonizing the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 55(3), 151-162. doi: 10.3138/cart.53.3.intro

Lucchesi, Annita Hetoevėhotohke'e. (2018). “Indians Don't Make Maps”: Indigenous Cartographic Traditions and Innovations. *American Indian Culture and Research Journal*, 42(3), 11-26. doi: 10.17953/aicrj.42.3.lucchesi

Lucchesi, Annita Hetoevėhotohke'e. (2018). “Indians Don't Make Maps”: Indigenous Cartographic Traditions and Innovations. *American Indian Culture and Research Journal*, 42(3), 11-26. doi: 10.17953/aicrj.42.3.lucchesi

Herman, R. (2008). Reflections on the Importance of Indigenous Geography. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 32(3), 73-88. doi: 10.17953/ aicr.32.3.n301616057133485

FIGHT AND FLIGHT. This was first thought to illustrate a battle, but it is now consideredmore likely to represent the mystical struggle against evil spirits by shamans in trance. The facsimile reproduction shown here-pencil, watercolor, and poster paint by R. Townley Johnson-is based on photographs and tracings of the original. Pakhuis Pass, Clanwilliam District, Western Cape. From Johnson, R. T. (1979) Major Rock Paintings of Southern Africa: Facsimile Reproductions, ed. T. M. O'c. Maggs. Cape Town: D. Philip, pI. 67 (p. 62) as cited in Harley, J.B & Woodward, D. (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

PAINTED PAWNEE CELESTIAL CHART ON TANNED ANTELOPE SKIN OR DEERSKIN. Originally belonging to the Skiri band of Pawnees, the chart was collected at Pawnee, Oklahoma, in 1906 as part of a sacred bundle. It may be a descendant of a precontact original. The Milky Way, which the Pawnees thought of as parting the heavens and as the pathway of departed spirits, is represented by small dots across the middle of the chart. Adjacent to the Milky Way is a circle of eleven stars known as the Council of Chiefs. The North Star ("star-that-does-notmove"), chief over the other stars, is among the largest. There are traces of three pigments: black, red, and yellow. Photograph courtesy of the Field Museum, Chicago as cited in Harley, J.B & Woodward, D. (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

MAP ROCK PETROGLYPH, SOUTHWESTERN IDAHO. The block of basalt is at the base of a 150-meter-high cliff 600 meters northeast of Givens Hot Springs, Canyon County, Idaho, on the north side of the Snake River. The "map" face is oriented toward the river and slightly upstream, so that it confronts anyone traveling down the valley.

"Although not provable, this is one of the more convincing examples of a map in rock art"

Photograph courtesy G. Malcolm Lewis. Lewis, G. Malcolm (1998). "Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

"Although not provable, this is one of the more convincing examples of a map in rock art"

Photograph courtesy G. Malcolm Lewis. Lewis, G. Malcolm (1998). "Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

SPECULATIVE INTERPRETATION OF MAP ROCK. On the left is a line drawing of Map Rock delineating and identifying selected features. On the right is a map of the corresponding area, which was occupied by Shoshones in early historical times. The interpretation is based in part on a letter from E. T. Perkins Jr. (1897) and on a typescript from]. T. Harrington (n.d.); Features 2-10 are hydrological, 11-14 are conspicuous peaks, 15-18 are watersheds, and 19-23 are animal figures. Lewis, G. Malcolm, (1998). "Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 51-182). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

CAROLINIAN STAR COMPASS. Carolinian navigators arrange lumps of coral, coconut leaves, and banana fibers on a mat to teach students the sidereal compass. In this compass from Satawal Atoll lumps of coral are laid out in a circle to represent the thirty-two compass points, but they are spaced unevenly since each one stands for the actual rising or setting point of the particular star or constellation. (Rising points are indicated by the prefix tan, setting by the prefix tubul; both with an a suffixed to bridge consonants.). Banana fibers strung across the principal axes demonstrate reciprocal star courses. A small canoe of coconut leaves in the center helps the student visualize himself at the center of various star paths. Bundles of coconut leaves placed just inside the ring of coral lumps represent the eight swell directions used in steering. Finney, Ben. (1998). "Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 443-492). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

SENSING AN ISLAND BY REFLECTED COUNTERSWELLS (left). SWELLS REFRACTING AROUND AN ISLAND (right). Swells also refract around an island, creating characteristic patterns of interference as they meet. After Lewis, D. (1994). We, the Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific, 2d ed., ed. Derek Oulton. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, p. 234. and p. 238 as cited in Finney, Ben. (1998). "Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 443-492). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

EXAMPLE OF A REBBELIB. Finney, Ben. (1998). "Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 443-492). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

REBBELIB: A MARSHALLESE STICK CHART THAT REPRESENTS THE ISLANDS OF ONE OR BOTH CHAINS.

"As with the other types of charts, the rebbelib were not consulted during voyages."

After Winkler, Captain [Otto?] (1901). "On Sea Charts Formerly Used in the Marshall Islands, with Notices on the Navigation of These Islanders in General," Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1899, 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. P 1:487-508, esp. 501 as cited in Finney, Ben. (1998). "Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 443-492). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

"As with the other types of charts, the rebbelib were not consulted during voyages."

After Winkler, Captain [Otto?] (1901). "On Sea Charts Formerly Used in the Marshall Islands, with Notices on the Navigation of These Islanders in General," Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1899, 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. P 1:487-508, esp. 501 as cited in Finney, Ben. (1998). "Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania" in J. B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Vol. 2 (3), pp. 443-492). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ books/HOC/index.html

A navigational chart from the Marshall Islands, on display at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. It is made of wood, sennit fiber and cowrie shells. From the collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. Date not known. Photo by Jim Heaphy. CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46844500

Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. Smithsonian Institution. 1882-’83. Washington, 1886. Government Printing Office. Page 90: ”The copy made by Lieutenant Reed was traced over a duplicate of the original, which latter was drawn on a buffalo robe by Lone-Dog, an aged Indian, belonging to the Yanktonai tribe of the Dakotas, who in the autumn of 1876 was near Fort Peck, Montana, and was reported to be still in his possession.” wikipedia

WOODEN MAP FROM GREENLAND. Kunit (1885). "Anecdotal descriptions of the maps online today compare them to some sort of archaic, ruggedized handheld GPS device: waterproof, small enough to fit inside a mitten, and naturally buoyant. It’s easy to picture a lonely seal hunter in his kayak using the map to navigate through an archipelago by the light of the moon.

check this out!

But this is how we use modern maps, as roadside companions, and suggesting that the Tunumiit used them the same way is nearly as Eurocentric as Hansen-Blangsted’s dismissal. There is, in fact, no ethnographic or historical evidence that carved wooden maps were ever used by any Inuit peoples for navigation in open water, and there are no other similar wooden maps like these found in any collection of Inuit material anywhere else in the world." https://www.atlasobscura.com/

check this out!

But this is how we use modern maps, as roadside companions, and suggesting that the Tunumiit used them the same way is nearly as Eurocentric as Hansen-Blangsted’s dismissal. There is, in fact, no ethnographic or historical evidence that carved wooden maps were ever used by any Inuit peoples for navigation in open water, and there are no other similar wooden maps like these found in any collection of Inuit material anywhere else in the world." https://www.atlasobscura.com/

"... we envision a future in which Indigenous communities formulate their cultural mapping programs in a way that protects and fosters cultural sovereignty, maps the Indigenous without leaving the Indigenous behind, and simultaneously transforms the way non-Indigenous people read, interpret, and make use of maps of Indigenous cultural knowledge."

Pearce, Margaret, & Louis, Renee. (2008). Mapping Indigenous Depth of Place. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 32(3), 107-126. doi: 10.17953/aicr.32.3.n7g22w816486567j. P. 123.